The Future Role of Satoyama Woodlands in Japanese Society

HIDEO TABATA

Introduction

Literally, sato means inhabited areas or villages, and yama means hills or mountains. Satoyama woodlands are areas of forest used by a particular village or community. Up until the 1960s, most Japanese woodlands (except those in very remote areas) had been used for many years to provide domestic and commercial firewood and charcoal, manure, edible wild plants, mushrooms, timbers, and other forest products. Satoyama woodlands were also repeatedly used for ‘slash and bum’ agriculture/shifting cultivation. These were generally of two types: those of deciduous oak composed mainly of Quercus serrata, and those composed of Japanese red pine (Pinus densiflora). Oak woodlands were regenerated by coppicing but red pine woodlands were usually reproduced by natural seeding or, sometimes, by afforestation. The Korean dongsan is almost identical to satoyama woodlands, but the coppice woodlands in England (Buckley, 1992) are not.

Coppicing to supply firewood and charcoal was the principal forestry practice in satoyama oak woodlands. However, most communities stopped using wood for fuel in the 1960s when propane gas became the standard domestic fuel even in rural areas. Charcoal production was remarkably reduced during the same period.

In rural Japan before the 1960s, wood for fuel and charcoal was obtained by cutting trees in satoyama woodlands every ten to twenty years. The shrub layer was very poor because shrubs were taken for firewood more often, although some shrubs were left as nutrient for the forests. The poor shrub layer and light forest floor provided good conditions for the growth of mushrooms and wild vegetables. Shrubs and leaf litter collected from the forest floor were used as manure for paddy fields but were replaced by chemical fertilisers in the 1960s. The poor soils in the Japanese red pine woodlands were good for the growth of some mushrooms such as Tricholoma matsutake.

Distributed in the satoyama area were bamboo forests, planted forests of Cryptomeria japonica and Chamaecyparis obtusa, and small patches of Miscanthus sinensis grassland for thatching. As mentioned above, the satoyama management was closely linked to the agricultural regime of paddy cultivation. The irrigation water for paddy fields or cultivated fields was supplied direct]y from satoyama woodlands or indirectly from irrigation ponds made in the satoyama area. It is difficult, therefore, to separate those woodlands from the agricultural lands located alongside them. Thus, satoyama is really an integrated landscape of woodlands, grasslands, bamboo forests, plantations, irrigation ponds, irrigation channels, paddy fields located next to the satoyama woodlands, the footpaths between them, and the like (Tabata, 1997a).

There are many differences between natural and satoyama woodlands. Within the latter there are various stands that are managed in different ways and are of different ages according to who owns them. Satoyama woodlands have a far simpler structure of stratification than their natural counterparts. Clear cutting is totally different from the gap formation in the natural forests. In satoyama woodlands, natural gap formation rarely happens and dead trees and fallen trunks are. seldom found. Man-made gaps of some extent are formed at regular intervals according to the duration of clear cutting rotation. Species replacement after clear cutting is limited in satoyama oak woodlands because of coppice regeneration. However, the species composition shows stochasticity in satoyama red pine woodlands because of the regeneration by natural seeding.

The method and extent of utilisation of satoyama woodlands were altered periodically by the demands of the local economy, for example, wood fuel supply for the small scale iron industry, commercial firewood supply to the urban area, grazing in the woodlands, and the like. However, those woodlands came under severe pressure or were exploited when a cash economy was introduced to the rural areas in the seventeenth century, after which they increasingly deteriorated (Chiba, 1956, 1990; Ogura, 1992, 1996). This exploitation consequently caused drastic changes in the landscape from satoyama woodland to barren land in many areas.

The use of satoyama woodlands in modern times also appears to have been very exploitative, and barren areas were widely distributed throughout Japan even at the beginning of the Meiji era (in the mid-nineteenth century). However, the barren lands were somewhat restored when the pressure on the. woodlands was decreased after the first fuel revolution in which coal and coal products were. introduced as domestic fuel, though the recovery process of the vegetation was not recorded. A change in vegetation type has been taking place in thesatoyama woodlands during these thirty v. ears following the second fuel revolution in the 1960s.

Many woodlands still retain the basic features of well managed satoyama woodlands, and constitute still the most common type. of vegetation in Japan, probably occupying over one-third of the total forest area. This coverage is despite the decline in satoyama woodland management and the related increase in abandoned or unmanaged satoyama woodlands over the past thirty years. It is also true that satoyama woodlands have been the most familiar natural environment for the Japanese people, who have enjoyed, for example, the changes in colour in autumn and springtime and on whose beauty much of Japanese culture is based.

The Current Situation

Satoyama woodlands have been destroyed by the expansion of cities, principally because over the past thirty years the woodlands have lost their commercial and forestry value. This however does not mean that the relationship between satoyama and humans has altered because of the recent changes in the Japanese lifestyle. The owners of satoyama sold them to developers without any consideration of their importance. Amongst other things, housing, factories, and golf courses have been built on satoyama woodlands. However, the benefit of these woodlands became clearly apparent when their destruction was followed bV. environmental pollution and disasters. Familiar plants and animals have been disappearing from our surroundings, and many of them, particularly inhabitants of the periphery of the satoyama woodlands, paddy field footpaths. artificial grasslands, wetlands, etc. are now vulnerable or endangered species (Tabata, 1997c).

Since biologists had not recognised the importance of the satoyama environment and woodlands, which had been disturbed by human activities and were, therefore, no longer in their natural state, satoyama has not been properly researched. We do not know the biological and ecological features of satoyama, and have only now started undertaking the necessary research on it in Japan.

The situation is very serious for those satoyama woodlands located on the hills of Pleistocene deposits as the topography of such land is easily modified into the flat lands by the use of construction machinery. The floral components of satoyama woodlands on the Pleistocene deposits are so rich that the destruction of those endangers more species than does that of the woodlands located in bedrock areas. Pleistocene deposits are principally distributed on the edge of plains and basins which also comprise heavily populated urban areas. Eventually woodlands that surround the urban areas tend to be destroyed for ‘development’ and the fragmentation of woodlands that development causes is another associated problem.

Paddy fields in small valleys surrounded by satoyama woodlands are usually less. productive and were amongst the first to be abandoned. Footpath vegetation, which was grown~ and maintained in connection with the management of paddy fields, was the first to be destroyed whenever mowing took place. Delicate wetland and water plants (such as Sanguisorba tenuifolia, Hosta longissima, Swertia cliluta, Nymphoicles peltata, N. indica, etc.), which survived in or around wet paddy fields formed on the clay layer of Pleistocene deposits were lost because many irrigation ponds were abandoned. Another reason was that there was no fluctuation of pond water level due to abandonment of paddy cultivation in some satoyama areas (Tabata, 1997c).

After abandoning the management of satoyama woodlands which have prevented ecological succession, unmanaged satoyama woodlands are now changing into evergreen broad-leaved forests comprising evergreen oak species and Castanopsis cuspidata. In the near future we might well be deprived of the pleasures of the seasonal changes in colour that satoyama woodlands bring. This may also mean a change in the Japanese perception of nature as, apart from the southern part of Japan, the deciduous, broad-leaved forests have been the major element in the Japanese landscape, Indeed, Yasuda (1980) has argued that Japanese culture has been based on the deciduous broad-leaved forests or woodlands since Neolithic times.

In addition, the neglect of bamboo forests has led to the invasion of satoyama oak woodlands by bamboo. This replacement has had very serious repercussions for biodiversity as bamboo forests support few other plant species. Moreover, this will lead to soil erosion and the other ecological difficulties after flowering, as bamboo plants are monocarpic and die after flowering. Owners of satoyama woodlands have not complained about the invasion of bamboo forests because they are essentially interested in the ownership of the land rather than in the continuance and maintenance of the woodlands.

Biological Characteristics of Satoyama

FLORA

Satoyama woodlands in the central part of Japan are very similar to the lowland and hill forests of Korea and the north-eastern part of China, although the number of tree species is greater in China and Korea. Quercus serrata is dominant in Japanese satoyama deciduous oak forests while deciduous oak forests in Korea and north-eastern China comprise other oak species such as Quercus aliena, Q. mongolica, Q. variabilis, Q. acutissima and, in China, Q. liaotungensis. On the other hand, the principal species of evergreen broad-leaved. forests are related to those in southern China and south-east Asia. These two types of forests appear to have a completely different history, although in Japan, satoyama woodlands are currently being replaced by climax forest of evergreen broad-leaved trees. In Korea and north-eastern China, where it is colder and drier than Japan, climax forests consist of deciduous broad-leaved trees containing several species of oak (Tabata, 1997b).

Our studies have shown that footpaths between paddy fields can be regarded as meadows, the. importance of which has not been recognised yet. Although the width of the footpaths is narrow, they connect to each other to form large areas of artificially managed meadows that have been maintained since paddy cultivation began. Many species growing on paddy field footpaths are found in the meadows of north-eastern China, especially in those of Inner Mongolia. Amongst others, Sanguisorba officinalis, S. tenuifolia, Gentiana squarrosa, Vicia psbudo-orobus, Lespedeza pilosa, Patrinia scabiosaefolia, Miscanthus sinensis, Phragmites communis, and Eupatorium lindeyanum are all found in meadows of north-eastern China. Lespedeza bicolor, Platycodon grandiflorum, Tllymus serphyllum, and Agrimonia pilosa growing on the fringes of satoyama woodlands are also found in the meadows of Inner Mongolia. Inula britanica, Aster fastigiatus, Phragmites communis, and Sium suave occur in Japanese wetlands or river beds and are also found in the meadows of north-eastern China. Sophora flavescens and Echinops which are found on artificial Japanese grassland also inhabits meadows in Inner Mongolia (Tabata, 1997b).

On the basis of the similarity of floristic components and physiognomy among Japanese, Korean, and north-eastern Chinese vegetation, it is possible to speculate that meadows similar to those of Inner Mongolia, and deciduous oak forests similar to those in Korea and north-eastern China, were found in Japan in the last-glacial period. Satoyama woodlands and paddy field footpath vegetation are therefore likely to be remnants of Inner Mongolian meadows and the deciduous oak forests of Korea and north-eastern China. This means that the artificially managed satoyama environment has maintained biodiversity of the last-glacial period even in the Holocene together with warm elements.

MUSHROOM FLORA

In Kyoto (central Japan) the mushrooms of the satoyama woodlands (Pinus densiflora and Quecus serrata woodlands) tend to emerge in autumn. They are basically boreal and are distributed in the temperate zone from Japan 'to the Eurasian continent through Korea. They are represented by Lyophyllum shimeji, Boletopsis leucomelas, Rozites caperata, and Tricholoma matsutake, On the other hand, the evergreen broad-leaved forests are dominated by tropical or subtropical mushrooms like Hymenogaster arenarius and Amanita perpasta whose fruit bodies emerge in midsummer.

Tropical or subtropical mushrooms grow in bamboo forests. Dictyophora indusiata, Cryptoderma asparatus, and Psilocybe lonchophorus are represented here and fruit bodies are found in hot summer. These species are generally confined to bamboo forests even though red pine and oak woodlands are located very closeby. Some species of mushroom are common to both bamboo and evergreen broad-leaved forests (Yokoyama and Sakuma, 1997).

ANT FAUNA

In Kyoto, satoyama woodlands are very rich in ant species because of the mosaic structure of the environment. It is remarkable that rare ant species. especially submerged species. are found in satoyama woodlands. They are represented by Discothyrea sauteri, Monomorium triiale, Pentastruma canina, Epitritus hermerus and E. hirashimai. Boreal species like Dilchoderus sibiricus inhabit oak woodlands whereas tropical or subtropical species such as Epitrutus hexamerus and E. hirashimai are found in bamboo forests. Evergreen broad-leaved forests are also inhabited by tropical or subtropical ant species (Onoyama, 1997). Just as the association between fungi and the host plants has been roughly maintained, so has the biological association between particular ant species and vegetation. This association has been maintained at least since the last ice age.

ECOLOGY OF POND-INHABITING INSECTS

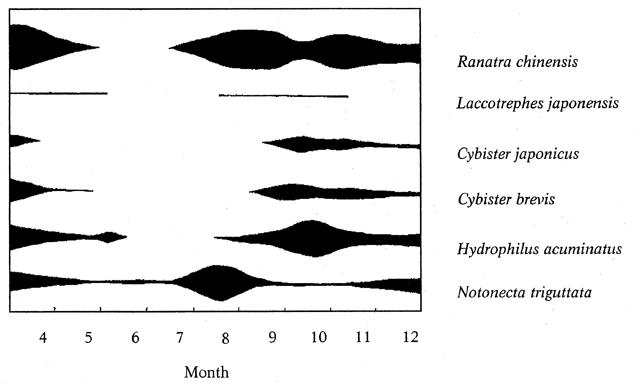

A comparison of the behaviour of various pond-living insect species was conducted in a pond in Nara, central Japan (Hibi. 1993; Hibi and Yamamoto, 1997). In early summer, most individuals of these species disappeared from the pond where they hibernated, though some individuals of Notonecta triguttata stayed throughout the year (Fig. 1). There were some differences in the time the species of insect left the pond and their duration of absence. Cybister brevis was the earliest to leave the pond and the last to return. By marking the insects it was shown that in summer they travelled to paddy fields 1–1.5 km away to reproduce. These insects cannot survive unless there are submerged paddy fields within a distance of 1–1.5 km from the pond; a combination of paddy fields and ponds is therefore essential for their survival.

Fig. 1: Seasonal occurrence of pond-inhabiting insects (Hibi, 1993)

ECOLOGICAL INTERCONNECTION

A good example of the ecological interconnection in the biological community is provided by Sophora flavescens, which grew abundantly in grasslands and was used for thatching and pasture for domestic animals and Shijimiaeoides divinus which only feeds on Sophora. As grasslands decreased in area and number, the population of Sophora decreased and this butterfly has now become an endangered species. It is perhaps ironic that both these species now survive on the practice fields of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces (Ishii, 1997).

Because trees and shrubs were removed from woodlands, the practice of coppicing reduced the fauna and flora in British coppice woodlands (Evans and Barkham, 1992). Although this observation may have important ecological implications for satoyama woodlands, similar studies have not been undertaken in Japan.

The Relationship Between Satoyama and People

It is important to note that satoyama woodlands should be maintained both for the conservation of biodiversity and an amenity for people, even though satoyama woodlands have now lost their economic value and there is little hope of changing the attitude of those who own them. Satoyama woodland management involved artificial disturbance of some scale in intervals of clear cutting rotation. which provided various habitats to the inhabitants of the areas. Charcoal production is in this sense the most attractive practice for the conservation of satoyama woodlands because the clear cutting for charcoal production can produce a mosaic structure in the woodlands. The problem is the cost of charcoal production. Charcoal can be put to various uses in the environment industry, which provides a sustainable use for it as an alternative to its use as fuel. There is a hope of developing large-scale. cheap charcoal production (Tabata, 1997d).

Small-scale electrical power production, which uses wood for fuel, is another new method that both uses woodland resources sustainably and produces a mosaic forest plan. It is also challenging as it depends on sources of renewable energy with a minimal detrimental impact on the environment. Besides, the heat efficiency will be about 85% in a small-scale biomass energy system when the heat is used for district heating and cooling as opposed to about 35% in large-scale electric power production in which heat is wasted, including the loss during electric transmission (Koike, 1997; Tabata, 1997d).

Who is responsible for the management of satoyama woodlands? I believe that so long as the owners of these woodlands continue to ignore their management we will need to introduce the concept of 'social commons', establishing that woodlands are for the use of the community as a whole (in the same way as schools, hospitals, public libraries, bridges. roads etc.). One way of achieving this may be to assign the care of private woodlands to local public forestry corporations or local forest owners associations in the form of contractual agreement with the owners in a transitional stage to full public management. Eventually, local governments should be responsible for satoyama woodlands although some management should be undertaken by the central government as these areas have many regulatory functions relating to the environment. In addition, I believe that only professionally trained forest workers belonging to governmental forest agencies, local public forestry corporations, and/or local forest owners' associations should be engaged in satoyama forestry.

Recent satoyama research has shown that this environment, as well as the adjacent agricultural environment, is necessary for the survival of many plants and animals, suggesting the kind of landscape arrangement that should be conserved in the future for the maintenance of biodiversity. Such a landscape would also constitute an. amenity for the Japanese people.

Many perennial herbaceous species found on paddy field footpaths are now vulnerable even though the footpaths are well managed and herbicides are not used. For example, it is no longer easy to find Gentiana scabra, Platycodon grandiflorum, or Eupatorium fortunei. It is also difficult to find them on the footpaths of abandoned paddy fields. Why are familiar autumn flowering herbaceous plants vulnerable on well-managed footpaths? It is possible that their disappearance is related to the introduction of early-ripening varieties of paddy rice. Farmers used to mow the footpaths before they harvested the paddy fields. The last mowing at the end of September, therefore, caused the most serious damage to autumn flowering herbaceous plants. Before the introduction of early-ripening varieties, these plants could flower, seed, and reserve the assimilation products before the last mowing. Moreover, while almost all rice varieties today are early-ripening species, farmers used to cultivate late-ripening, mid-season-ripening, and early-ripening varieties. The abandonment of paddy fields located next to satoyama woodlands seriously affected herbaceous plants because the footpaths also became neglected. It is thus essential to restore paddy fields as an agricultural environment for environmental sustainability, landscape and biodiversity.

There are some delicate political and economic problems here, and we may need a political decision to restore the abandoned fields. We could introduce concepts such as the ‘Kleingarten’ in Germany (Toshitani and Wada, 1994) and open up the fields to the public for the restoration of the agricultural environment under a contract between the owner and the new cultivator. Many city dwellers. and active retired people are seeking land to undertake agricultural activities. In conclusion, it is also important to recall the intimate relationship between human beings and nature, especially woodlands/forests. Human sensibility is developed in the. cradle of nature, especially woodlands/forests. In the forests there are various kinds of sounds, smells, colours, and shapes which cannot be artificially created. We can experience and develop all sorts of senses in the forest. This experience is very important in the infant stage of ontogenetic development of human beings. We may need to increase the opportunities for children to develop a contact with nature and spend time in the natural settings of woodlands/forests, for healthy development. Woodlands/forests are an essential human amenity and important -for our well being and healthy development because they generate a sense of peace and amity when we are there and even when we view a landscape with forests. It is therefore imperative for the present and future generations that we preserve satoyama in our living environment.

References

- Buckley, G. P (ed.), (1992): Ecology and Management of Coppice Woodlands. Chapman & Hall, London.

- Chiba, T. (1956): Studies on Barren Hills. Gakuseisha, Tokyo (in Japanese).

- ——— (1990): Studies on Barren Hills (rev. ed.), Sosiete, Tokyo (in Japanese).

- Editing Committee of Natural Geography of China, Chinese Academy of Sciences. (1988): Natural Geography of China,Vol. 2, Science Publisher, Beijing. (in Chinese).

- ——— (1980): Vegetation of China, Science Publisher, Beijing (in Chinese).

- Evans, M. N. and J. P. Barkham, (1992): Coppicing and Natural Disturbance in Temperate Woodlands:A Review. pp. 79–98, in G. P. Buckley (ed.), Ecology and Management of Coppice Woodlands, Chapman & Hall, London.

- Hibi, N. (1993): Nature of Satoyama, Gonta, 3(2): 4–5, 3(3): 2–3 (in Japanese).

- Hibi, N. and T. Yamamoto (1997): Pond-Inhabiting Insects in Satoyama, pp. 78-81, in H. Tabata (ed.), Satoyama and Its Conservation, Hoikusha, Osaka (in Japanese).

- Ishii, M. (1997): The Change of Butterfly Fauna in Satoyama, pp. 126–132, in H. Tabata (ed.), Satoyama and Its Conservation, Hoikusha, Osaka (in Japanese).

- Koike, K. (1997): Satoyama Woodlands Can Supply Clean Energy of Carbon Dioxide Emission Zero. pp. 194–6, in H. Tabata (ed.), Satoyama and Its Conservation, Hoikusha, Osaka (in Japanese).

- Ogura, J. (1992): History of Human Beings and Landscape, Yuzankaku, Kyoto (in Japanese).

- ——— (1996): Life of the Japanese Viewed from the Vegetation in Meiji Era, Yuzankaku, Kyoto (in Japanese).

- Onoyama, K. (1997): Characteristics of Ant Fauna of Satoyama, pp. 66–9, in H. Tabata (ed.), Satoyama and Its Conservation, Hoikusha, Osaka (in Japanese).

- Red Data Book Committee, (1989): Red Data Book of Japan, Japan Association of Natural Conservation, Tokyo.

- Tabata, H. (1997a):What Kind of Nature is Satoyama? pp. 6–9, in H. Tabata (ed.), Satoyama and Its Conservation, Hoikusha, Osaka (in Japanese).

- ——— (1997b): Flora of Satoyama. pp. 35–43, in H. Tabata (ed.), Satoyama and Its Conservation, Hoikusha, Osaka (in Japanese).

- ——— (1997c). Loss of Irrigation Ponds, Paddy Fields and Grasslands, and Endangered Species, pp. 118-125, in H. Tabata (ed.), Satoyama and Its Conservation, Hoikusha, Osaka (in Japanese).

- ——— (1997d): Our Proposal From the Viewpoint of Satoyama Research, pp. 164-75. in H. Tabata (ed.), Satoyama and Its Conservation, Hoikusha, Osaka (in Japanese).

- Toshitani, N. and T. Wada, (ed.), (1994): A Vision of Realization of Japanese Kleingarten, Gyosei, Tokyo (in Japanese).

- Yasuda, Y. (1980): Introduction to Environmental Archaeology, NHK Publishing,Tokyo (in Japanese).

- Yokoyama, K. and D. Sakuma, (1997): Characteristics of Mushroom Flora of Satoyama, pp. 50-57, in H. Tabata (ed.), Satoyama and Its Conservation, Hoikusha, Osaka (in Japanese).